Paris climate change targets likely to be missed

Global targets to limit climate change are unlikely to be met due to delays in changing human land uses, according to an international team of scientists led by Dr Calum Brown at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology. Writing in the journal Nature Climate Change, they argue that efforts to make land management less damaging to the climate need to be stepped up dramatically if high levels of climate change are to be avoided.

The Paris Agreement to limit average global temperature increases to 1.5⁰C above pre-industrial levels relies heavily on changes in the management of agricultural land and forests around the world. Many countries plan to prevent deforestation or establish new forests over large areas to absorb carbon dioxide from the air, and to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture. These planned changes would remove up to 25% of the greenhouse gases released by human activity every year.

However, this new research shows that such changes in land use usually take decades to occur, far too slowly to make the required contribution to slowing climate change. According to Dr Calum Brown, “The 195 countries that signed the Paris agreement in 2015 set out a range of actions they would take to tackle climate change. In most cases little progress has been made in implementing these actions, and often the situation has actually worsened in the last 3 years. Our research suggests that many of the plans for mitigation in the land system were unrealistic in the first place, and now threaten to make the Paris target itself unachievable.”

In particular, the research highlights deforestation in tropical regions, which has accelerated recently after previously slowing down. Professor Mark Rounsevell, a co-author of the study, warns that “ongoing destruction of tropical forests in Brazil, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Indonesia is particularly concerning, because these forests store huge quantities of carbon, as well as containing high levels of biodiversity. Attempts to protect these forests have had limited success, and laws against felling have recently been rolled back. Political and economic pressures make it very difficult for governments to stop deforestation and start reversing past damage”.

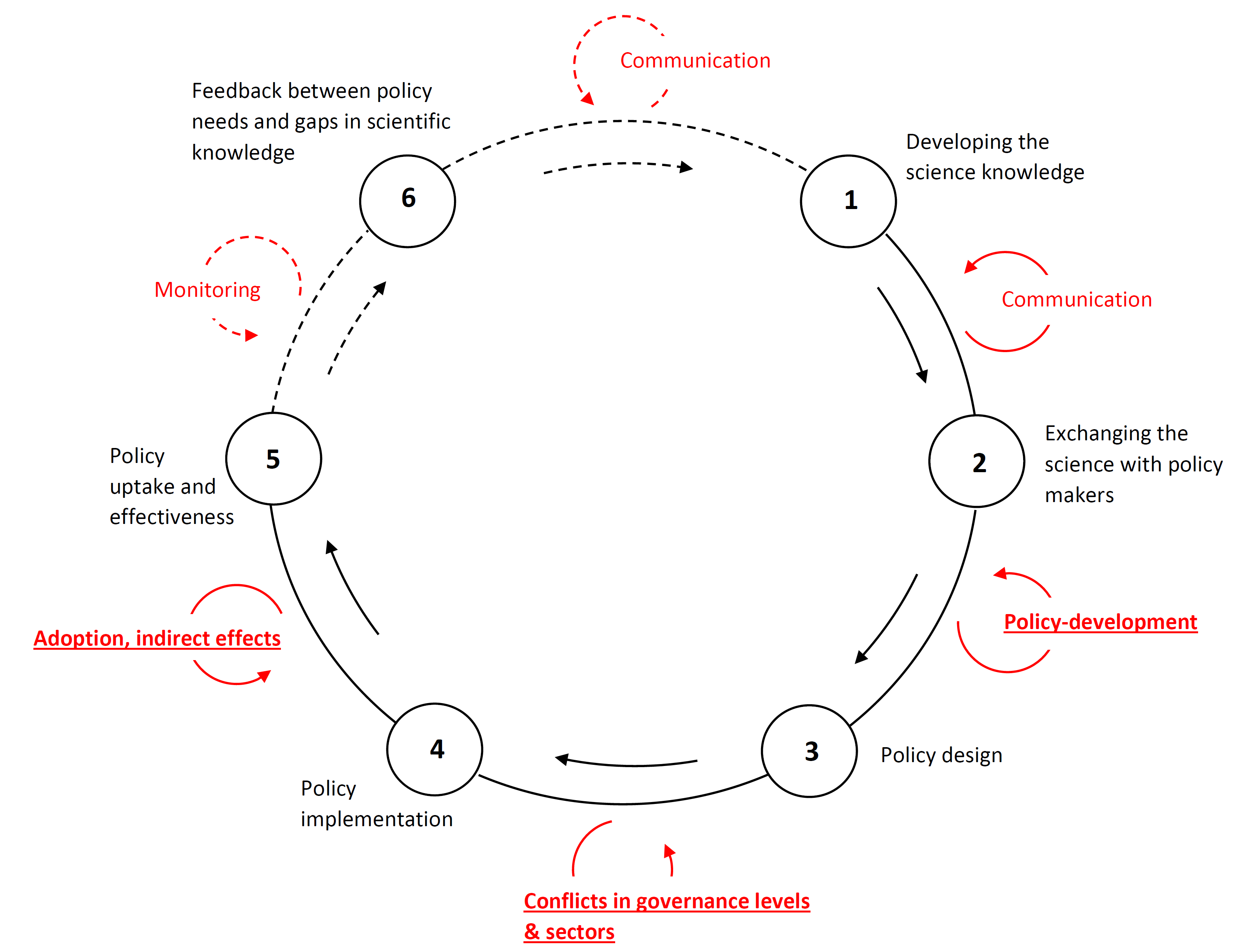

The slow rate of progress is, the researchers argue, an inevitable consequence of disconnected political priorities, delays in the adoption of new approaches by land managers, and trade connections that drive deforestation in tropical countries. Even in countries like EU Member States, with strong legal systems and deep commitments to climate mitigation, these factors have made progress far too slow.

Dr Peter Alexander, an author of the study from the University of Edinburgh, said “individual countries’ plans to accomplish the Paris Agreement are vague, almost certainly insufficient and unlikely to be implemented in full. Richer countries have not been leading the way, either in reducing their own emissions or in reducing the pressure on developing nations. We need to find rapid but realistic ways of changing human land use if we are to meet our climate change targets”.